A thing I like to do on occasion is review board games (and, technically, card games too). I’ve done many over at my main blog, and I think it will be fun to do it on occasion here as well. So if you’re interested in learning about some of the many high-quality (and, let’s be honest, not-so-high-quality) games out there, keep your eyes on this space and we’ll see how many we can cover! We’ll start with a game I learned to play last week: Tzolkin: the Mayan Calendar (which is technically spelled Tzolk’in, but I’m going to make things easier on myself and leave out the apostrophe).

A thing I like to do on occasion is review board games (and, technically, card games too). I’ve done many over at my main blog, and I think it will be fun to do it on occasion here as well. So if you’re interested in learning about some of the many high-quality (and, let’s be honest, not-so-high-quality) games out there, keep your eyes on this space and we’ll see how many we can cover! We’ll start with a game I learned to play last week: Tzolkin: the Mayan Calendar (which is technically spelled Tzolk’in, but I’m going to make things easier on myself and leave out the apostrophe).

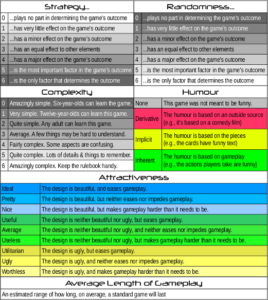

First things first, though: I like to use a different rating system than most. I was contemplating review articles (not just for games, but for films, music, and other things), and it occurred to me that these articles only describe how the author of that article felt about that particular game/film/book/album/etc. Such articles don’t leave any room for the subjective tastes of others. So I decided to create a rating scale that evaluates each aspect of a game objectively. It ranks the game in six areas: Strategy, Randomness, Complexity, Humour, Attractiveness, and Average Length of Game Play. This allows you to decide if a game is right for you based on your personal preferences. It looks something like this:

Let’s look at the ratings for Tzolkin:

Strategy: 5

Randomness: 1

Complexity: 5

Humour: None

Attractiveness: Pretty

Average Length of Gameplay: 2 hours

Tzolkin is a worker placement game with a unique and innovative mechanic based on the Mesoamerican concept of time. The pre-columbian peoples saw time as a series of cogs, rotating against one another as the days passed. To simulate this, the game board has a large gear in the centre which rotates several smaller gears around it The worker pegs are placed on the outer gears. After each turn, the central gear is rotated one notch, which in turn rotates all the other gears one notch, moving your workers further along the path of available actions.

To play Tzolkin, players take turns either placing their worker pegs (which represent actual workers) on one of the outer gears, or removing them. You can place or remove as many as you want on a turn (you start with three, but can gain up to three more later on), but you must do one or the other. You can’t do both, and you can’t do neither. Thus, careful and meticulous planning and a good deal of foresight are essential to this game.

Each of the outer gears represents a temple at a Mesoamerican site, such as Palenque, Tikal, or Chichén Itzá. Each one offers different sorts of actions; one allows you to harvest corn (which in most ways works as currency, but is also necessary to feed your workers four times throughout the game), one allows you to collect resources (such as stone, gold, or crystal skulls – which, thankfully, have nothing at all to do with the most recent Indiana Jones film), one allows you to use stone, gold, and corn to build buildings and/or gain technology advances, one allows you to get more workers or use corn to buy or sell resources or gain additional favour with the gods, and one allows you to deposit a crystal skull to rise in the standing of one of the gods (once a crystal skull has been used on a space on this gear, that space is no longer available to any player).

When you place a worker, you must place it on the lowest available space on that gear. The lower the space, the lower the benefit, and the higher the space, the higher the benefit. If space 0 is occupied, you must place your worker on space 1. If both spaces 0 and 1 are occupied, you must place on space 2, and so on. However, you must spend corn equal to the number of the space on which you are placing the worker, in addition to the normal cost to place workers (you can have one worker on the board for free, but if you place a second worker on either this turn or any subsequent turns, you must spend a corn, and a third worker costs a total of 3 corn, and so on in an Fibonacci progression).

Thus, you are likely going to have to place a worker low on the gear and wait a few turns until it reaches the space you want to use. This gets complicated because you’re not allowed to pass; you may have to take a few low-level actions on other gears whilst you wait for that one worker to get to the action you really want… But when you remove a worker from a gear, you take the action marked on the corresponding space on that gear.

This sounds pretty complicated, and it kind of is, even though I’m leaving out a lot of detail. This feeds into my usual complaint about worker-placement games: remembering how the different available actions work, and remember which actions are available. However, the game is very thinky-thinky, and I do appreciate that aspect of it. But my biggest complaint with Tzolkin comes from the fact that I’m a stickler for detail with just enough knowledge about Mesoamerican cultures to be dangerous: some of the aspects of this game are not accurate. For example, although the game is billed as The Mayan Calendar, the large central gear is embossed with an image of the Aztec Calendar Stone (which, in addition to not being Mayan, isn’t even a calendar; it’s just a cover stone. It’s only called that because it has the glyphs for the months on it. It wasn’t used to keep track of the days of the year. I know it’s not an important point, but it still bugs me).

So I’d say that Tzolkin is not my favourite game, but I’d be willing to play it again in the future in the right circumstances. But that’s just my opinion; you should look at the ratings above and the description I’ve written so you can decide for yourself! Until next time,