Last week, we began looking at the essentials of designing your campaign. It was a big topic, so I had to split it into two sections. Today’s entry will finish what we started, as we look at the remaining three basic campaign arrangements. In case you’ve forgotten, last week we discussed the ‘Episodic’ and ‘Set-Piece’ design systems. Today, we will cover ‘Branching,’ ‘Puzzle Piece,’ and ‘Enemy Timeline.’

Last week, we began looking at the essentials of designing your campaign. It was a big topic, so I had to split it into two sections. Today’s entry will finish what we started, as we look at the remaining three basic campaign arrangements. In case you’ve forgotten, last week we discussed the ‘Episodic’ and ‘Set-Piece’ design systems. Today, we will cover ‘Branching,’ ‘Puzzle Piece,’ and ‘Enemy Timeline.’

Branching Campaign

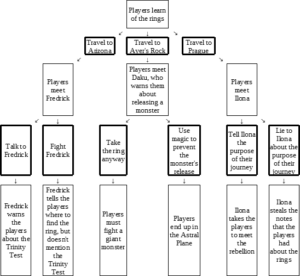

Whereas the Set Piece design has a series of scenes that will happen in a certain order, the Branching expands that idea by creating a number of scenes that may or may not happen. The players’ actions and the success or failure they experience determine which scenes occur, and in what order.

In the Set-Piece design, scene #2 will always occur after scene #1. The only difference is how quickly and easily the players get from 1 to 2. By contrast, the Branching campaign design is more like a Choose Your Own Adventure book, where the players may choose whether to go from scene #1 to scene #2 or scene #3. Alternately, the players may go to scene #2 if they are successful in scene #1, but will go to scene #3 if they fail in scene #1.

Let’s look at an example of this. We’ll say that the players are a group of wizards serving as faculty members at a Scottish university in early 1945. They’ve discovered that the Germans are looking for a series of brass rings which are scattered around the world. Once assembled, the rings will reveal the location of a powerful magical artefact. The players must find these rings and get the artefact before the Germans do. Our branching design might look something like this:

The players’ choices and actions determine the course of the campaign. This gives the Branching style the advantage of being almost completely player-driven, instead of GM-driven. The downside is that the GM will have to plan a lot of events and encounters that the players will never see.

Puzzle Piece Campaign

A compromise between the Set-Piece style and the Branching style is the Puzzle Piece. Like the Branching style, events and encounters won’t be experienced in a specific order like Set-Piece scenes are. But rather than planning out each possible event, he has a list of specific information or events, and marks them off as they come up.

As an example, let’s look at the 1945 campaign setting described above, listed as puzzle pieces:

- One ring is located at the Trinity Test Site

- Fredrick, a government agent stationed near the test site, knows about the ring and the upcoming test

- One ring is at the top of Ayer’s Rock

- Daku, an aboriginal tribesman, knows that removing the ring from Ayer’s Rock will break the spell that has kept a giant monster trapped in an inter-dimensional pocket realm

- Ilona, a woman working with the anti-German rebels in Prague, can put the players in touch with the rebellion

- A member of the rebellion knows that one of the rings is hidden in an abandoned amusement park on the edge of town

And so on…

As the players encounter these people or experience these events, you can mark them off your list so you know what the players have done and learned so far.

Enemy Timeline Campaign

The final system we’re going to look at is the Enemy Timeline. With this campaign style, you create a timeline of when the antagonists will complete certain events. Then, as the players perform their actions, you simply keep track of how long it took them to do this. You compare the timeline of the players to the pre-planned enemy timeline, so you know where the antagonists are and what they are doing whenever the players are taking actions. If the players show up at a place at the same time as the enemies do, then they can encounter those enemies.

In a lot of ways, this is the simplest campaign system to use outside of the Episodic approach. But it doesn’t always lend itself well to story-based games. It might work as a compromise between story-based games and combat-based games, if you have both Butt-Kicker and Storyteller gamer types in your group.

A Few Final Words on Campaign Design

There is one last approach to designing a campaign: improvisation. I used to rely on that a lot. I’d have a general idea of what the story was, and where I wanted it to go, but then I’d leave the details fuzzy and plan to wing it when time came. That approach may work for some people. I’ve learned, however, that it doesn’t work for me. Without specific plans and outlines, my stories would tend to wander and players would lose interest (and let’s be honest; I’d lose interest too!). So be very careful if you decide to run your game on the fly.

Of course, you will certainly have to improvise on occasion. Every now and then, your players will throw you for a complete loop; they’ll do something that you had no expectations of them trying at all. For example, I was once running a game in which I wanted to introduce an important NPC. I had a back story to explain why the NPC was there wanting to work with the players. But after the players heard the NPC’s story, they began discussing abandoning the main storyline and investigating the NPC’s backstory. As they asked questions about the NPC’s history, I had to create information out of the air on the fly.

We’ll talk about preparing for improvisation in a later entry. But for now, I think I’ve done a decent job of describing the main ways of preparing a campaign for your players. Next week, I’m attending GenCon, so I won’t be able to do another entry until afterwards. So I’ll see you back here in two weeks, and until then, remember to